To do, or not to do.

Unlike Hamlet’s entirely existential question, mine is more of a kinetic quandary, requiring action, in one form or the other.

We had landed into Reykjavik the previous evening, after a long flight from Hong Kong via London, and although confronted with the singularly good news that the hotel had upgraded us into a suite, had just about enough energy to mutter “Yay!” and fall into bed. But not before looking out and marvelling at the carpet of white that covered everything, even the huge ships up on the slips in the harbour, just outside our floor to ceiling windows.

I have woken up around 4 am feeling exceedingly warm. Trust the Icelanders to turn up the heat inside and provide cozy duvets that all but make you sweat, I think. I can’t go back to sleep, and the suite means that I can wander out into the sitting space and sit awhile without disturbing the Husband.

After amusing myself by looking out into the Reykjavik night and trying to spot other nocturnal life with the telescope standing against the window, I realise that I am still quite warm. And now there are the beginnings of stomach cramps.

By the time the Husband is awake and preparing himself for the day ahead, things haven’t improved much. And this is where the quandary rears its head.

We are scheduled to begin our two and a half week trip around the entire island of Iceland that day, returning to Reykjavik only at the very end of the trip. No matter how much I may want to crawl into bed and stay there, sticking around is simply not an option.

And of course, we are kicking things off by visiting Thingvellir. Where I am scheduled to do a winter snorkel at Silfra.

Those who know me well will know that I am quite risk averse. Yes, I’ve rafted down rivers, and abseiled down cliff faces and jumped out of airplanes, but all of those came after a significant amount of very unpleasant to watch bouts of freaking out, cold sweats and insides turning to a quivering mass of jelly and all that. I’m also hooked though, to the high that comes after you do challenge yourself in that way and conquer your fear, which is why I push myself into scaring me shitless. These are victories that are hard fought for, harder than you will ever know.

Silfra is the only place in the world that you can swim, snorkel or dive between two tectonic plates. Most intersections of tectonic plates usually occur deep within the earth’s crust, and the fissures are usually on the sea bed, making it difficult to get to. Due to Iceland’s tumultuous geological history, the fissure between the European and North American plates is actually at the surface, providing easy access to even novice snorkelers and divers.

Who wouldn’t want to explore such an opportunity? However, my usual excitement is tempered by four simple facts :

A. It is bloody winter. We are talking about getting into glacial water and staying in it for up to an hour. In Winter.

B. An earlier diving experience at the Great Barrier Reef hadn’t gone quite to plan, and even though I’ve had amazing experiences thereafter, that one still resurfaces in my memory every time, if you’ll excuse the pun.

C. Given the sudden onset of these weird symptoms, I’m not exactly feeling in tip top shape

D. Did I mention it is WINTER!

“Cancel it”, says the Husband, as he dons the first of several layers of thermal clothing. Averse to any and all water related activities, he hasn’t signed up for the adventure. While I am going to be freezing my ass off in the water, he is going to be walking around in relative comfort, taking in the spectacular scenery and absorbing the huge cultural and historical significance that Thingvellir has for the Icelandic people.

“I don’t think I can get a refund if I cancel this late in the day, and it’s quite an expensive activity”.

“You’re right, don’t cancel it”.

Yeah, thanks for nothing.

“Have some breakfast, maybe that will help”, he continues, practical as ever. But he has a point. Maybe some food will help.

It doesn’t. I manage to quaff something from the buffet, but as departure time rolls around, I’m not really feeling much better.

Promptly a few minutes before 9, both a weak sun, and our beaming guide Julli peek into the hotel lobby. A huge bear of a man, armed with the number one Icelandic winter face protection device – a beard, he had picked us up at the airport the previous day, and is going to be with us for the duration of the trip. This is the same funny, gentle and kind man who will sit patiently with me at the doctor’s office a couple of days later, even as the Husband is outside chasing photographs of a perfect Icelandic dawn. At my behest, I hasten to add, lest you jump to any conclusions.

But this is Day 1, Hour 1. I imagine the scorn with which this rugged Icelander will greet the news of my wanting to cancel the very first thing on the schedule, a real once-in-a-lifetime experience, all because I’m “feeling under the weather”. Experience an Icelandic winter indeed. Wimps!

I decide that I will ease into it. I slide gingerly into the back seat, saying things like “Oh, I didn’t sleep very well, I’m so tired”, and so on, trying to lay the groundwork for my eventual refusal.

Of course we get there in record time, and of course we are early, so Julli suggests we walk around a bit, while he gives us the abridged version of the history of Thingvellir. Needless to say, I keep looking for a suitable interjection point, but don’t find one.Shortly after, Julli walks us up a track and we emerge in a little clearing, where two vans belonging to Dive Iceland are parked. The crew is already hard at work laying out the equipment, and other people, my fellow snorkelers by the looks of it, are milling about, waiting to begin.

Julli introduces me to the diving guide, an avuncular looking Swiss man named Rudy, who shakes my hand heartily before turning back to overseeing the preparations. “Now, tell him now”, I’m saying to myself but before I can open my mouth he turns around suddenly and in a booming voice, tells everyone to gather around. After the usual welcome note, he suddenly looks at me and says, “You, whats your name?”

I tell him, and he says, “Can you come up here for a moment please?” I go forward and he tells me to take off my jacket and parka. I look at him as if he is crazy, but he just looks back at me as if he has made the most reasonable request in the world. The rest of the group is looking on and waiting, so I remove my outer layers.

Here comes the cold, eviscerating any sense of warmth from just a couple of seconds ago, and all the more severe for the sudden change.

Even as I stand there, he turns me around to face the others and says, “So, as you may have noticed, it is winter in Iceland. And some of you may be wondering how were are going to snorkel in such weather. Don’t worry. We have all the equipment that you need to have a safe and comfortable time, starting with our special wetsuits here. Now, they have to be put on it a very specific way. I am going to demonstrate on our charming volunteer here-“, pointing at me, “-exactly how we put it on so that we stay warm and dry once we get in the water”.

Well that’s just peachy. I can’t bloody well cancel now, can I?

I look to the back to see Julli moving off with the Husband who is giving me a thumbs up sign, even as he disappears from view around the bend.

“Shoes off please”, commands Rudy, bringing me back to my predicament. I stand there in my totally inadequate merino wool socks, wondering what else he is going to have me take off. There really isn’t much else left. The crew in the meantime is handing out wetsuits to the rest of the group after sizing them up, who begin their own acts of stripping away jackets and shoes.

Thankfully, that is the very last of the disrobing. What follows next involves putting things on, not taking things off, in what can only be described as something equivalent to the stuffing of a giant sausage.

The wetsuits that Dive Iceland uses are padded neoprene, and they are are a single piece of non elastic hell. After struggling to pull the suits up to the waist, there is a complicated manoeuvre that involves much contortion to get the suit up to the neck with the arms fully extended into the two sleeves which end in gloves, all one piece. The area around the wrists and neck is then sealed tightly, but we are warned that water is still likely to get in. Great.

Then you need the help of a partner, mine being Rudy of course, to yank the hood over the head from behind, in a move almost guaranteed to give you spondylosis, so as to snugly fit around the skull. On top of all this goes the life jacket, and the snorkelling mask and tube. Needless to say, by the time we are done, we look like a bunch of Michelin men dressed in frog suits.

Then we waddle, there’s really no other word for it, down the track and to the entry point into the water, where a ladder has been suspended. Just before we descend, we put on a pair of flippers. You try wobbling down a ladder in flippers that are 10 times the size of your feet, encased in a thick rubber stocking, with anything resembling grace. It can’t be done, I assure you.

I’m clearly teacher’s pet for some reason, and therefore I lead the group down the ladder and am the first in the water. This is where the first of my fears is demolished; I really cannot feel the cold. The inside of the wetsuit is warm, and the only chill I feel comes from the cold wind hitting the exposed skin on my face, and the inevitable drops of water that seep into my hands, just as Rudy had warned us. I am so struck with how comfortable it is that I look up in surprise, only to see that the Husband has ambled back to take photographs of me in my padded glory. And I can’t even wave him off for fear of getting even more chilly water in my hands.

By now the entire group is in the water, and Rudy hustles his way to the front of the pack. The fissure is not very wide, and there is a slow, gentle current that takes the glacial melt along it before it empties into a large lake. Because of the slow current, you really don’t need to do much other than just float along, and you can stop anytime and grab hold of the rocks at the side if you want to take a small break from the floating.

As we set off, we take a few minutes getting used to the incredible buoyancy of the suits. You literally cannot drown in them, and that makes swimming in the normal sense, both impractical and unnecessary. By the time we get the hang of it, we are in the middle of the fissure.

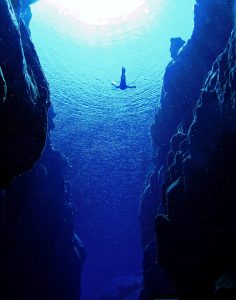

“Look down”, said Rudy. I do. And then I forget everything else.

The first thing I register is the cold, yes, as my face goes under the water. And then, the deepest, bluest blue, that goes on and on under me. I am suspended over, no, I am in a chasm whose bottom I can barely see. All I can see are the rocks of the walls on either side fading into nothingness in that unreal blue. There is no sound, hardly any movement but for the few strands of algae drifting around. The blue is punctuated by shots of vivid green of the moss growing on the rocks. There are no fish, no coral, no signs of visible life.

Even as we move along, the chasm widens and deepens. The bottom falls away and I am suspended over a huge cavern, extending miles down. It feels as if I am floating in a huge underwater cathedral. I could worship at one such as this, I think, the idea bringing a smile to my face.

In a flash I realise my mistake, hard learnt from the Great Barrier Reef, that of making sure your lips stay puckered up, no matter what. Water immediately enters my mouthpiece, and I raise my head hurriedly and begin to take out the mouthpiece and tilting the mask to clear the water.

“You don’t need to do that”, says Rudy, who has spied me grappling with my mask. “This isn’t sea water, it’s glacial melt. So just swallow it. Its only the most pure water you will ever drink”.

So it’s not cold, well not very cold, and I don’t have to worry about water in my face. This is just getting better and better. Coupled with the fact that when I grip a rock on my left, I am touching America, and when I move over and touch one one the right bank, I am touching Europe. How cool is that! Rudy floats back and forth, taking pictures of the group. I try to keep my hands from shaking, so I can take stills with my underwater camera, and quickly give up after a few quick shots, when I realise that every movement of my hand means more water in the glove.

I cannot remember how quickly the time flies by, and it seems that we have only just begun, when the scenery under us shifts and we begin to see the first signs of a sandy bottom, signalling we have entered the lake.

At this point, Rudi makes sure that we stay well to the left, so that we are not swept out into the lake with the current, requiring a long and tiring swim back to shore. At one point, we stop and anchor ourselves on to the rocks at the side while we try to flip over and dive into the water. The suits make it very hard going indeed and even after releasing the pressure by jiggling the buoyancy device, it takes a fair amount of vigorous kicking to even manage to dive.

And then it is over. The ladder that ascends up to the ground can be spied in the distance, glinting in the soft, mid morning light. I am reminded anew of how quickly I become used to the grace that suffuses my every move in the water and how much I resent the return to my klutzy, stumbling about on dry land.

I’m out first and I take off the flippers. Standing in my wet socks does not bother me much now, for some reason. I reach forward to help another one of our group exit the water and she slips on a patch of hard ice, pulling me down with her. What would have otherwise resulted in broken hips is only a cause for laughter as we roll about on the ground in our padded suits, until others come forward, lending us a hand to rise, guffawing good-naturedly.

We return to the vans and perform the disrobing and robing in reverse. My fleece, parka and gloves begin their work of restoring warmth to my body, but they don’t have to work too hard. I am lit from within.

I see Julli striding down the path, coming to get me. The Husband is waiting at a viewpoint over Thingvellir. I look out at the frozen landscape, seeing it’s beauty in that stunning winter light, for the first time since morning.

“So”, smiles the Husband. “You did it”. Yes, and as usual, I’m so glad I did.

The cramps subsist for a few more days, but vanish before the week is out. I’d like to believe the magical glacial water had something to do with that.

This is how, what I suspect will be a a life long love affair with Iceland, begins.

I never knew this was possible! How amazing and wonderful – I found it pretty damn fascinating to just gaze at the open chasm at Thingvellir; I can’t imagine the thrill of swimming in there with a hand on each continental plate. Very cool – thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

It was truly incredible. I found myself wishing I could have done a proper dive, but you need to have a PADI certificate to be able to do so, so it was just the snorkel for me. Still, a memorable experience that I’m glad I persisted with. And I’m glad you enjoyed reading it. What an incredible country!

LikeLiked by 1 person